I’m not going to lie. I signed up to watch this film because I’m a complete nerd, and I like Shaker-style furniture. I figured I would sit through a period piece I’d be acutely interested in and then go on with my day. I got more than I bargained for — in a good way. The Testament of Ann Lee is the second collaboration between director Mona Fastvold and writer Brady Corbet. Their first foray together brought us The Brutalist in 2024, a bracing story and a deeply personal passion project.

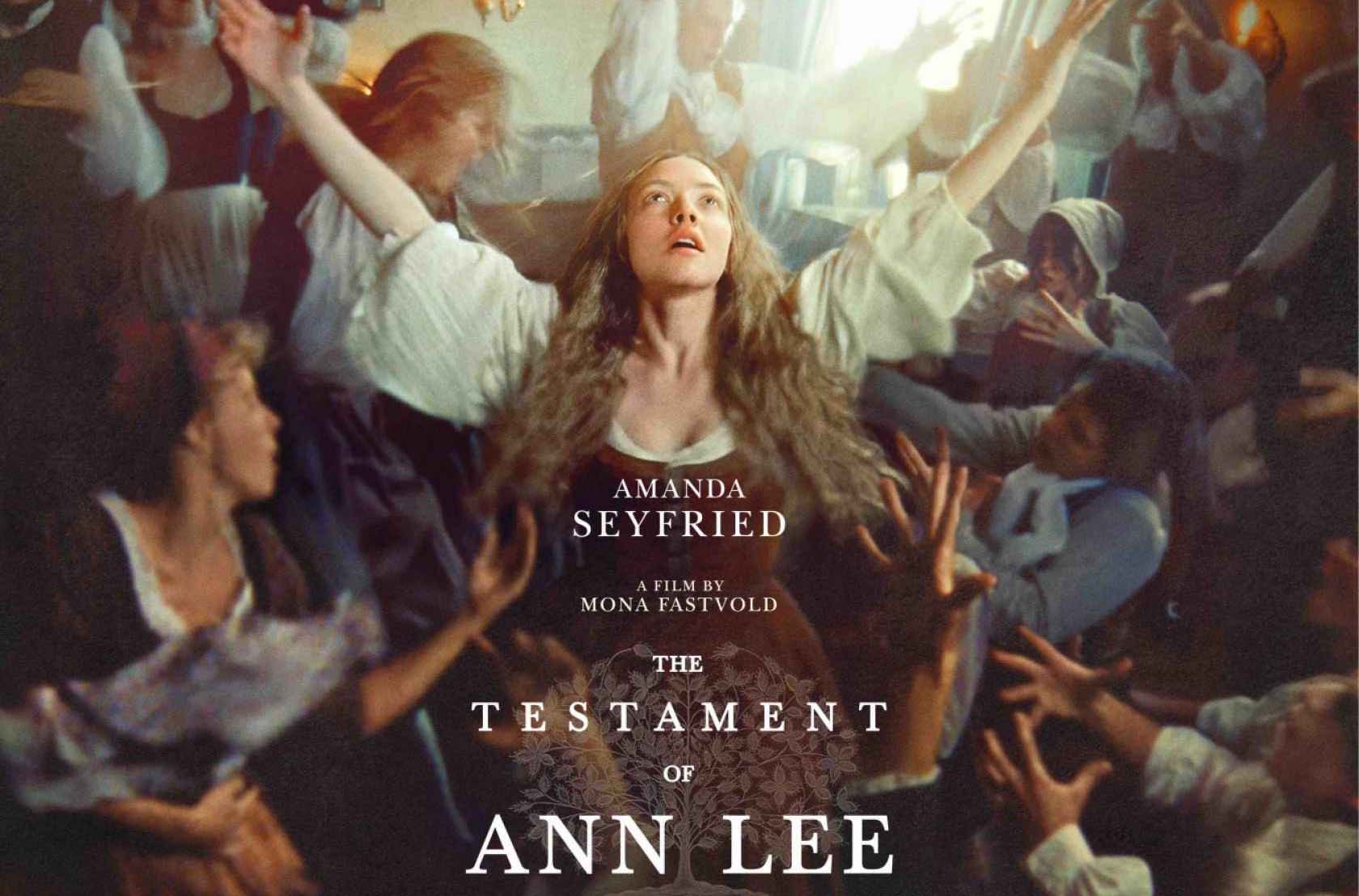

If you are not as much of a nerd as I am, you might not know who the Shakers were. I love woodworking and furniture, and Shaker furniture is a coveted style that still inspires design today. But who were the Shakers? They began as an 18th-century religious movement sometimes described as a precursor to Pentecostalism. Shakers were known for physically demanding worship. They shook, danced, convulsed and exhausted themselves in pursuit of spiritual purity, and Fastvold captures those rituals with startling immediacy. Working with choreographer Celia Rowlson-Hall and Oscar-winning composer Daniel Blumberg, she stages these ceremonies as something like part rave, part rapture. The film is technically a musical, but not in the Broadway sense. There aren’t any big, crowd-pleasing ballads. Instead, the songs feel like chants or prayers adapted from Shaker hymns. What does this have to do with furniture? The Shakers weren’t just radical in their theology. They were revolutionary in the way they worked. Long before Henry Ford standardized the assembly line, the Shakers were developing early mass-production techniques, designing furniture and tools that could be made efficiently, repaired easily and replicated with remarkable consistency across their communities.

So I went into this film for the wrong reasons, but I came away with a powerful insight into the people themselves and their founder, Ann Lee, played by Amanda Seyfried.

We see Lee’s neglected youth and a life defined by suffering. After living with emotionally distant parents, she enters into an ideologically abusive marriage marked by brutally sad and repeated miscarriages. We don’t just see personal loss; we see the power others have over her and her lack of agency in her own existence. The film’s most powerful stretch comes while Lee is confined to an asylum. It’s here that she solidifies the radical religious visions she believes God has given her. From there, Lee’s message — centered on gender equality, communal living and the radical claim that she embodies Christ’s second coming — begins to spread.

To say her movement ruffled feathers would be an understatement, and what begins as mockery escalates into persecution. For about an hour, The Testament of Ann Lee feels close to something truly great in its depiction of Shaker communities. That focus starts to slip once the film broadens its scope. Supporting characters like Lee’s brother William, played by Lewis Pullman, and benefactor John Hocknell, played by David Cale, pull the narrative outward, but not always to its benefit. A rare moment of levity comes with Hocknell’s musical number about finding land for the first community, but it feels out of place and mostly highlights how humorless the rest of the film is. Plenty of fascinating questions are raised in the second half. Can Lee’s teachings survive her death? What about the fact that she can’t read? Does it even matter? And how does a movement built on strict chastity survive without constant recruitment? Unfortunately, the film doesn’t linger on these ideas long enough to provide real clarity before heading toward an ending steeped in violence and loss. It feels like the movie never quite gets where it wants to go, but that may be appropriate. The Testament of Ann Lee is a flawed but deeply compelling film. It was well worth the watch. I give it a solid 7/10.