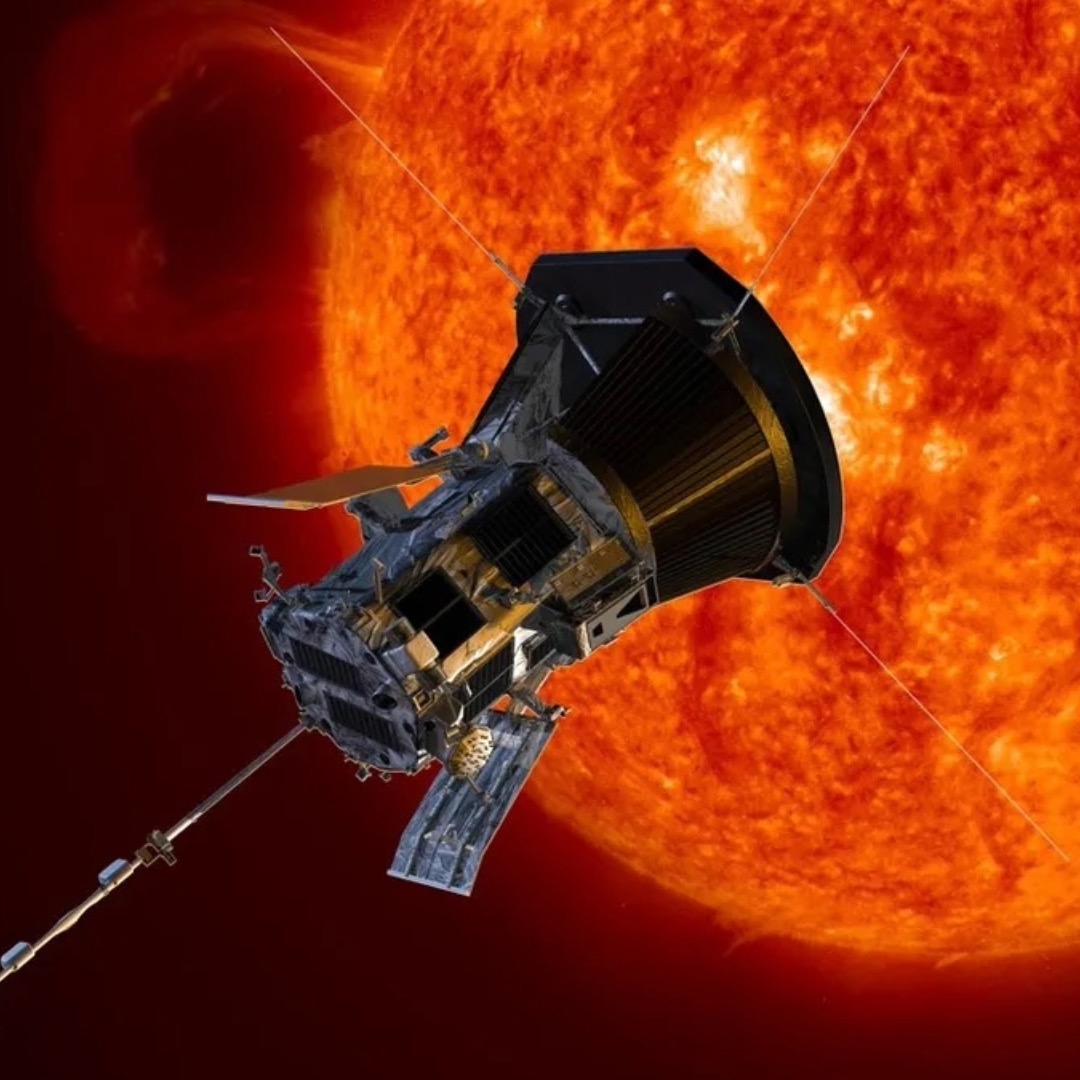

The spacecraft flew within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the solar surface to “touch the sun” on Christmas Eve.

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is alive!

Two days after an historic Christmas Eve sun flyby that flew closer to the star than any spacecraft in history — taking the car-sized spacecraft nearly 10 times closer to the sun than Mercury — the Parker Solar Probe phoned home for the first time since its solar encounter. The spacesent sent a simple yet highly-anticipated beacon tone to Earth just before midnight late Thursday (Dec. 26).

Scientists on Earth were out of contact with the Parker Solar Probe since Dec. 20, when the spaceraft began its automated flyby of the sun, so the signal is a crucial confirmation that the spacecraft survived, and is in “good health and operating normally,” NASA shared in an update early Friday (Dec. 27).

Mission control at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland received the signal just before midnight ET on the night of Dec. 26, the statement read.

The spacecraft is programmed to send home a more detailed status update on New Year’s Day, Jan. 1. It’s only then that scientists will know whether the spacecraft indeed collected the expected observations of the sun from the flyby, Michael Buckley, a spokesperson at JHUAPL, which oversees the Parker Solar Probe mission, told Space.com in an email. “This gives the team a better picture of overall spacecraft and subsystem/instrument health, including whether Parker’s data recorders are full.”

The probe should transmit the bulk of the images and science data in late January, when it will have swung away to a safe distance from the sun.

Around 6:53 a.m. EST (1153 GMT) on Christmas Eve, the spacecraft accomplished what it was designed for: It swooped to within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the sun’s surface. And it did so while traveling at a whopping 430,000 mph (690,000 kph) — breaking its own personal best as the fastest object ever built by human hands.

“It’s just a total ‘Yay! We did it’ moment,” Nicola Fox, NASA’s associate administrator for science missions, said in a video update on Dec. 24.

The fact that the spacecraft survived such a close pass by the sun is a testament to the mission team’s engineering, including a custom, 4.5-inch-thick heat shield and an autonomous system that protects the probe from the sun’s intense heat while allowing it to point toward our star and let the coronal material touch the spacecraft. While the heat shield allows the spacecraft to endure temperatures up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,371 degrees Celsius), the probe likely ended up experiencing lower — but nevertheless sizzling — temperatures of up to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (980 degrees Celsius), the mission team has previously said.

“No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star, so Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory,” Nick Pinkine, the Parker Solar Probe mission operations manager at APL in Maryland, said in a Dec. 20 statement.

Since its launch in 2018, the Parker Solar Probe has helped decode longstanding mysteries about our star, chiefly why its outermost layer, the corona, gets hundreds of times hotter the farther it moves from the sun’s surface. Enroute to the sun, the probe serendipitously also caught rare closeups of passing comets and shed light on how Venus, Earth’s hellish twin, may have lost its water.

On Christmas Eve, scientists expect Parker to have flown through plumes of plasma still attached to the sun. It may have also observed different types of solar winds and solar storms thanks to ongoing increased turbulence on the sun’s surface, the mission team told reporters earlier this month at the annual AGU meeting.

“We can’t wait to receive that first status update from the spacecraft and start receiving the science data in the coming weeks,” Parker Solar Probe program scientist Arik Posner at NASA Headquarters in Washington said in the statement.

Parker Solar Probe has phoned home!

After passing just 3.8 million miles from the solar surface on Dec. 24 — the closest solar flyby in history — we have received Parker Solar Probe’s beacon tone confirming the spacecraft is safe. https://t.co/zbWT7iDVtP

— NASA Sun & Space (@NASASun) December 27, 2024

From Space.com